Reviews

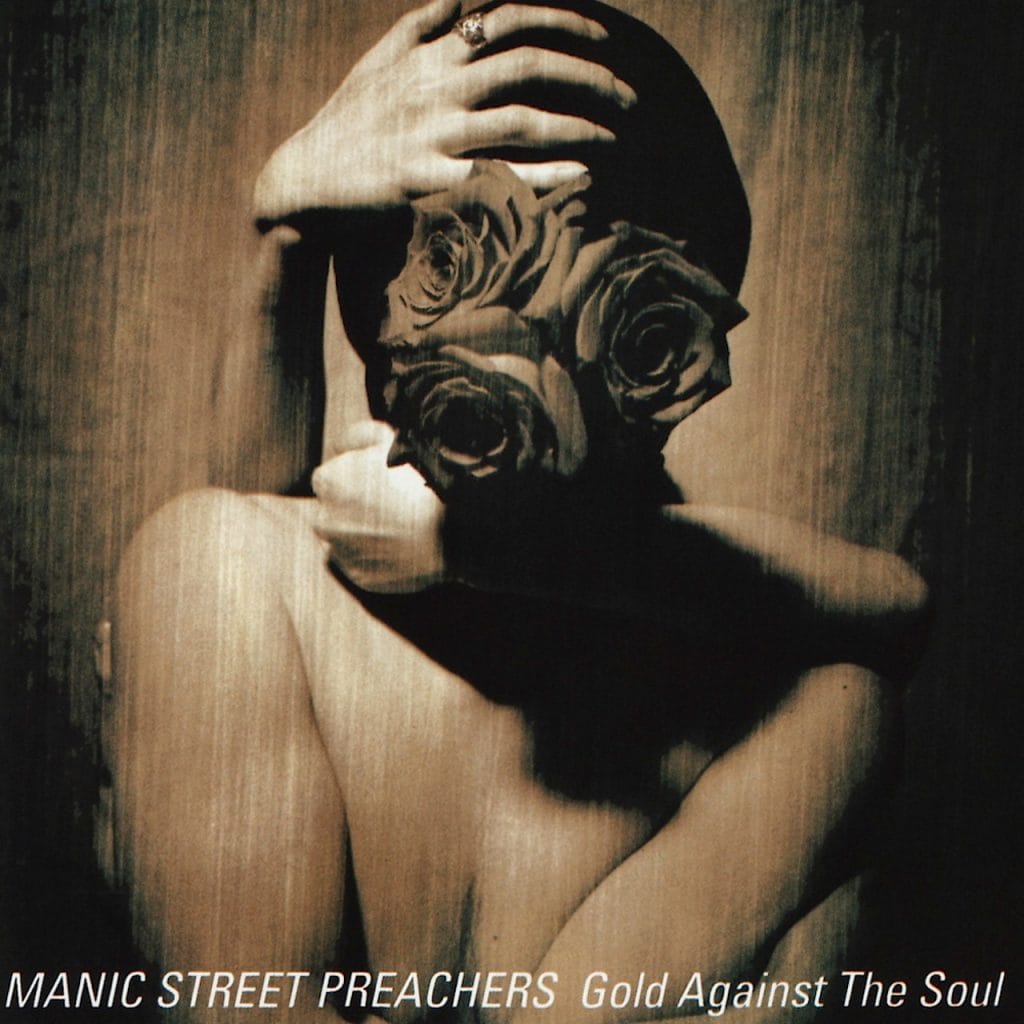

Manic Street Preachers, Gold Against the Soul

Stereodista revisits the second record from the enduring revivalists

Popular culture is positively littered with a litany of references to time warps: whether this be that garish Richard O’Brien track, or the even more tacky Glee rehash thereof; Donnie Darko or Doctor Who. But were time a 12” record, who’s to say it would sit flat on the platter of your preferred turntable, in any case? It is of course a fluid construct, defined and constantly redefined by context, perception, and such. By definition, it is warped. And how firmly we grip time varies wildly from one person to another: I, for one, have allowed much too much of it to slip through my fingers; not least in this current lockdown. My very favourite band, the Manic Street Preachers, have not, however.

Generation Terrorists, a tumid pastiche on Guns N’ Roses’ odious histrionics, was released in 1992, when James Dean Bradfield, Nicky Wire, Richey Edwards and Sean Moore were in their nascent 20s. To labour the point a tad, I’d not done a lot by that temporal milestone. And to render the contrast that bit more stark still, before the ’90s were out, the South Walian lot had punted a further four records up and out between the two figurative uprights. These included their scabrous best, The Holy Bible (1994, and released a mere six months or so before Edwards’ disappearance), as well as the both critically lauded and commercially lucrative Everything Must Go (1996) and This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours (1998). And mine is thus: it wasn’t so much my mum’s tolerance of the latter’s lead single, as her addiction to it which had me hooked. Because of one knackered old cassette, her firstborn would be next to subscribe to these irreligious Gospels According to Nicky and Richey, who over the years have – occasionally together, yet primarily apart – written the always tortuous, sometimes tortured words around which James’ riffs and Sean’s fills worm and writhe. I will come to the fourth release in due course...

“So God is dead, like Nietzsche said,” or Bradfield sang on 1985 from the widely lambasted 2004 full-length, Lifeblood. (I may be contrary by nature, but I genuinely believe Empty Souls, I Live to Fall Asleep, and Solitude Sometimes Is to be among their better recorded outpour from this particular century.) But then he also conceded they’d “realised there’s no going back,” within that same chorus. And this is is, essentially, what the Manics have now been doing for donkeys’ years: in 2012, they may not have put even a faint trace of lipstick back on, but they rereleased their aforementioned début, Generation Terrorists. Remastered reissue, boxset teeming with nonessential ephemera, et cetera. Two years subsequent, The Holy Bible rose again in even more thoroughgoing a going-over, with a remastered reissue, boxset teeming with nonessential ephemera; three gruelling, if glorious December nights at the Roundhouse (“The ghost[s] of Christmas ha[d] come!”), with another the following summer at Cardiff Castle. Then, the turn of Everything Must Go. Again, remastered reissue, boxset teeming with nonessential ephemera; two aestival evenings at the Royal Albert Hall and, further away, a joyous 25-song set at the Liberty Stadium, Swansea. Perhaps God lives on, after all...

Fast-forward a further twelve months, and Send Away the Tigers – awash with songs so devoid of excitement, they sounded decidedly like a band entering, if not exiting the autumn of its time – had been remastered and was duly reissued, but no celebratory tour ensued. Another year on, and This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours gets the treatment: remastered reissue, two nights at Shepherd’s Bush Empire the ensuing summer, with a return to Cardiff Castle also covered. But what made these two lattermost rereleases that bit more intriguing was the changing, or churning up of previously immortalised tracklists: in the case of Send Away the Tigers, the lumbering, bland Welcome to the Dead Zone – once a lowly B-side to the similarly vanilla Your Love Alone Is Not Enough – replaced the chugging Underdogs, while a reworking of John Lennon’s Working Class Hero was salvaged from beyond that tedious silence which used to fester at the end of CD running times; a truly redundant adjunct. (Disclaimer: I cannot abide cover versions featuring on original releases.) Meanwhile with This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours, the honky-tonky, killer Prologue to History substituted the far inferior filler that was Nobody Loved You, although this revising – rather than merely revisiting – their previous sat uncomfortably with me. These discarded songs were, and remain, of their time; their claim to minutes on their respective albums, and many more of the lives of their listeners, as valid now as they were then, regardless of personal taste. And their replacement tends to disrupt a flow known and long since established in hearts, minds, ears and so on, making costly reissues lose some, if not most of their more intrinsic value.

Hindsight may be 20/20, but it's blindingly obvious that too much retrospection, in 2020, isn’t necessarily such a good thing. And if by now you’ve discerned notes of disdain, then it’s because – ’Tigers banished – the Manics still have some exceptional songs in them: for instance, the Richard Hawley-featuring Rewind the Film from the largely acoustic curveball album of the same name (2013), served up as a sort of unexpected sequel to James Dean Bradfield’s solo début, The Great Western; The Next Jet to Leave Moscow, from the jarring-yet-rewarding follow-up, Futurology (2014), is perfectly crafted indie-pop replete with self-deprecating throwbacks to the band’s landmark Cuba gig in 2001 and a trademark solo; International Blue, an homage to Yves Klein and his notorious #002fa7, was born arena-ready and duly did the business in the Spring/Summer 2018 stint. There have, therefore, been releases between the rereleases, and I would sooner hear those than have to fork out another £40 for a record I already own. (Yes, I fully grasp both the concept of capitalism and the grim irony therein, given the band’s once-vocal aversions to “this wonderful world of purchase power.”) But the Groundhog Day vibe has come to be a theme, to the point of becoming more of a focus than it should be. And in keeping with this deeply entrenched penchant, on June 12th of this year, to commemorate its 27th anniversary (yes, really), the aforesaid fourth – Gold Against the Soul – is to rouse from its ’93 slumber.

It may not be their best, but it’s certainly important: a marked improvement upon their histrionic introduction, it paves the way for the trenchant musicality of The Holy Bible, and frequently hints at the mordant commentaries which came with it. “Morning always seems too stale to justify/ Lament blossoms, hours minutes of our lives/ Broken thoughts run through your empty mind/ At least a beaten dog knows how to lie,” begins its opening number Sleepflower; the butt of many a jokey heckle for much too long. Dave Eringa’s production sounds dated, sure, but as lyrics concerning “endless hours in bed” proceed candid references to anxiety, its sentiment certainly doesn’t.

Its singles, well, they’re something of a mixed bag: the baggy La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh) is a “relic” less welcome in the modern-day; Life Becoming a Landslide slips too happily back into GNR parody, yet is redeemed by the immortal leitmotif, “My idea of love comes from a childhood glimpse of pornography”; Roses in the Hospital, with its sampled percussion and wah-wah guitar, recalls Happy Mondays as readily as it does Stay Beautiful, its foremost legacy the spawning of the “forever delayed” mantra. But its fourth and final one, From Despair to Where, remains a thing of true beauty, as sardonic lyricism (“I try and walk in a straight line/ An imitation of dignity”) meets some of Bradfield’s very best fretwork. Ever fleet of finger, he flits between squealing flair and blue-collar lug, as Nick Ingham-arranged strings lend a grandiose drama that is their very own.

Elsewhere, Yourself unapologetically apes Bon Jovi’s Livin’ On a Prayer, mimicking its central refrain – albeit transposed up a semitone or three, yet when the blueprint was so overly bombastic to begin with, it sort of makes sense. Less so Nostalgic Pushead, memorable only for its sensational opening gambit – “I am the raping sunglass gaze/ Of sweating man and escort agencies” – and intimations toward the work of Luis Buñuel. Symphony of Tourette, meanwhile, carries with it a thick whiff of fake Cali glam à la Jane’s Addiction, and this clings slightly looser to a bloated title track, too. Admittedly, after Life Becoming a Landslide, its quality rather falls off the ol’ proverbial cliff, with Drug Drug Druggy the main offender.

That being said, it is – and is so unmistakably – a product of its time; and in this forthcoming reissuing, it is to be presented as such. However, where it transcends its situation in ’93 lies in its lyrical fascination with the whiling away of “endless hours in bed” (Sleepflower), whence From Despair to Where was once ostensibly written “alone”, and where “so much fun” is to be had if Drug Drug Druggy is to be believed. Now, of all times, this viewing of time as some kind of nothingness – an inescapable void that needn’t be filled wisely nor with anything necessarily of real meaning – is highly relatable, albeit in a completely incompatible context. Thus if the music is largely ‘of its time’, then lyrically, this is ‘timeless’ stuff in more ways than one.

Is this, Gold Against the Soul, now more relevant than ever, therefore? Maybe, but to reiterate: it is not their finest hour. Yet gripes aside, yes, I have inevitably preordered another record I already own. And whether this should take in any one of London’s diminishing number of venues, or somewhere more enormous in South Wales, I now impatiently await the announcement of an extensive retrospective tour for when the lockdown has been unlocked, and our time – and our personal, warped perceptions thereof – has once more been freed.